Fédération internationale de football association (“FIFA”), with its prerogatives in creating the legal framework for the game of football, enacted new changes in their FIFA Football Agent Regulations (“FFAR”). To create a more transparent, efficient, and just system, the new regulations aim to reinforce contractual stability, protect the integrity of the transfer system, and achieve greater financial transparency. However, some of the introduced provisions may potentially violate competition laws, leading to a reluctance among many countries to incorporate the FFAR into their national regulations. With many court proceedings in various national courts from England to Brazil and before the Court of Arbitration for Sport (“CAS”), FIFA had to act to have consistent rules governing the January 2024 transfer window. Consequently, FIFA temporarily suspended the FFAR worldwide to prevent any uncertainty or inequality worldwide, hoping for a resolution to this matter rendered by the European Court of Justice (“ECJ”).

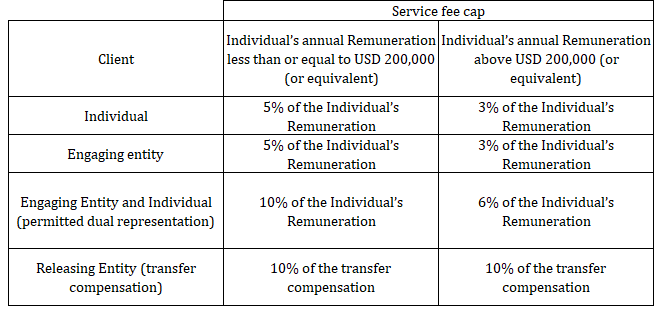

The changes were enacted at the end of 2022, with many taking effect at the beginning of 2023. The changes are numerous, but the most conspicuous ones pertain to introducing a service fee cap. The rules concerning the service fee cap have raised concerns regarding their compliance with the competition laws of various countries. The maximum fee for providing football agent services (irrespective of the number of football agents providing their services to the client) depends on the individual’s (player’s) annual remuneration.

Before we discuss the competition concerns, it may be useful to provisionally define the relevant market, which is the forefront issue of any competition case. The relevant market for the purpose of this discussion is the global market for providing football agent services.

The following discussion will use the pertinent provisions of EU competition law because most European countries have modeled their competition framework pursuant to famous Articles 101 and 102 of the Treaty on the functioning of the European Union (“TFEU”).

The FFAR rules have raised serious competition concerns, particularly in relation to due date regulations, debtor determination, claim to remuneration not yet due, settlement, prohibition of multiple representation, etc. However, the service fee cap contained in Article 15 of the FFAR has garnered the most attention.

Namely, Article 101 (1) (a) TFEU stipulates:

(a) directly or indirectly fix purchase or selling prices or any other trading conditions;

[emphasis added]

Although professional sports associations may have idealistic goals, they are regularly considered as enterprises in the sense of competition law. A 2005 judgment of the European General Court (at the time called “the Court of First Instance”) in the case Piau v. the Commission found that national football associations and FIFA constitute undertakings because they perform an economic activity.

The adoption of the FFAR rules can be considered a decision by an association of undertakings within the meaning of Article 101(1) TFEU, as FIFA and its member associations coordinate the behavior of their members (clubs and players) by adopting these rules. Subsequently, by qualifying the FFAR as a decision by an association of undertakings, further examination of competition infringements is possible.

The FFAR rules can potentially restrict competition within the meaning of Article 101(1) TFEU because they limit the economic independence and freedom of choice of undertakings affiliated with the association (in this case, FIFA) concerning the engagement of agents. Furthermore, the players’ agents are constrained and cannot act freely in the market since they can no longer negotiate their fees independently. Since the FFAR covers the whole (worldwide) market for procuring football players, agents have no alternatives. Finally, the agents who would elect to act contrary to the provisions of the FFAR can be sanctioned pursuant to Article 21 of the FFAR. Therefore, it may be argued that the FFAR establishes a cartel.

Another possible competition concern is that FIFA may have a so-called “collective dominant position” in the relevant market for football agent services.

The first paragraph of Article 102 TFEU reads as follows:

Any abuse by one or more undertakings of a dominant position within the internal market or in a substantial part of it shall be prohibited as incompatible with the internal market as it may affect trade between Member States.

In Compagnie Maritime Belge Transports and Others v Commission, the Court of Justice determined that a group of undertakings hold a collective dominant position when the companies present themselves or act together on a particular market as a collective entity. The undertakings must have economic links which permit them to work collectively. To establish the existence of these links, the following conditions, as outlined in Airtours v Commission, must be satisfied:

The FFAR may very well present an economic link between undertakings operating in the relevant market since they are binding on member national associations, football clubs, players, and the agents, which are moreover subject to sanctions where they infringe the FFAR that may even lead to their exclusion from the market. As a result, the conduct of these bodies is linked in the long term.

Interestingly, FIFA is not present in the global market for providing football agent services since it is neither a manager, player, nor a club. However, in the mentioned Piau case, the General Court found that FIFA has a collective dominant position in that very market because:

Therefore, if we apply the standards devised by EU courts, FIFA can be deemed to hold a collective dominant position in the relevant market.

In July last year, CAS decided that the new FFAR rules do not breach competition law. The dispute before the CAS involved the Professional Football Agents Association as the appellant and FIFA as the respondent. In its award, the CAS reasoned that, although the FFAR rules were in breach of both Article 101(1) and Article 102 TFEU in a manner as presented above, they were, nonetheless, compatible with the “regulatory ancillary restraints” framework devised in the Wouters case and Meca-Medina case, i.e., the FFAR rules were consistent with Article 101 (3) TFEU.

Namely, the CAS, invoking EU case law, acknowledged that anti-competitive conduct, which is liable to infringe Article 101(1), may be justified if the conduct is:

In the present matter, the CAS found that “FIFA may, in adopting the FFAR, justifiably pursue public interest objectives recognized by the EU legal order, even if the contested provisions of the FFAR may be liable to infringe EU competition law, so long as the FFAR provisions are appropriate and proportionate to achieve the intended objectives.”

The service fee cap changes are yet to be implemented in many national football associations, as the compliance of the FFAR with the standards of competition law has come into question before the national courts of many countries.

In England, the Football Association (“FA”) has declared this regulation incompatible with British competition law. Many leading football agencies in England challenged the FFAR and the FA Rule K Tribunal, stating that these regulations are non-compliant with the Competition Act of 1998. The Tribunal also pointed out that the other key provisions were sustainable, including those preventing agents from representing multiple clients in a transfer and requiring that the client pays the agent. However, implementation is not feasible due to the service fee caps.

Furthermore, a Spanish Commercial Court has issued provisional measures against implementing the new FFAR rules, halting their incorporation in their national regulations, based on Article 101 TFEU and Article 1 of the Spanish Competition Act. The court reasoned that these kinds of limitations could have a destructive impact on the viability of the business model of the football agents, with the addition that implementing these kinds of rules would represent an infringement of Articles 101 and 102 of the TFEU.

On May 24, 2023, the District Court of Dortmund declared a preliminary injunction preventing new changes from taking effect in Germany. The preliminary injunction was justified on the grounds that these kinds of regulations are opposed to the EU competition law. FIFA respected the injunction and implemented significant measures to avoid further ambiguity. Consequently, the German National Football Association’s obligation to implement changes in national football agent regulations is suspended, with the ongoing football transactions associated with them considered to have the same effects as before the implementation of the new rules. This decision elicited contention in football and opened the doors for suspending the FFAR worldwide.

The situation in other countries varies, with many not taking an explicit stance until the ECJ rules on this matter.

Two applicants lodged a claim for an injunction against FIFA before the Mainz Regional Court regarding the infringement of Articles 101 and 102 TFEU. The first applicant is a players’ agent and, in addition, vice-president of the players’ agents’ association, the Football Forum. The second applicant is a limited liability company that also acts as a players’ agent and is pre-registered with the German Football Association. The Mainz Regional Court referred the case to the ECJ. Given that the decisions regarding the FFAR are conflicting, the ECJ ruling will be significant. The primary role of the ECJ is to interpret EU law. A ruling that can set an authoritative interpretation of the new changes and its compliance with EU Competition Law could end this ongoing discrepancy.

The ECJ would need to scrutinize the FFAR to ascertain their proportionality and necessity in achieving FIFA’s legitimate objectives, such as safeguarding sports integrity and protecting athletes. The assessment would discern whether the regulations primarily constitute reasonable measures or serve as commercial restrictions that excessively curtail competition. The evaluation would also consider the regulation’s broad applicability across member states, aligning with EU law’s objective of promoting the free movement of services and the freedom of establishment. Should the ECJ determine that the regulations infringe on EU competition law, FIFA must revise and align them with EU competition law principles.

On December 30 of last year, FIFA announced that it approved the worldwide temporary suspension of the FFAR rules affected by the District Court of Dortmund decision until the ECJ renders a final decision in the pending procedures concerning the FFAR. FIFA also recommended that its member associations temporarily suspend the equivalent provisions from their national football agent regulations.

The Football Association of Serbia has already faced similar challenges regarding the service fee caps for football agent services.

In 2017, the Football Association of Serbia passed the Intermediary Engagement Rulebook (Pravilnik o radu sa posrednicima), which sets service fee caps for intermediaries (football agents) in Article 23. Pursuant to Article 23, if an athlete or an engaging entity hires an intermediary to facilitate a transfer, an intermediary’s service fee may not exceed 8% of the athlete’s total income. Similarly, if a releasing entity hires an intermediary, an intermediary’s service fee may not exceed 8% of the transfer fees paid for a transfer.

Was this provision ahead of its time with its promotion of the legitimate objectives of the Football Association of Serbia, or was it just a plain infringement of competition law? Only time will tell.

Overall, the proposed changes of the FFAR created a stir in the football community and divided opinions of national courts and arbitral tribunals. With many countries adopting different approaches to implementing the new regulations, the need for a consistent interpretation of the proposed changes has never been more crucial. We will have to wait and see the final ruling of the ECJ on this matter, as its decision will have substantial importance in applying competition law in the realms of the football transfer market.

Authors: Vuk Leković, Dušan Jablan, Marko Jović